- Home

- Sharyl Attkisson

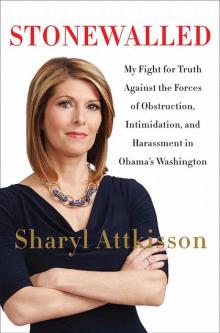

Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's Washington

Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's Washington Read online

DEDICATION

The truth eventually finds a way to be told.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With much appreciation to: the journalists who shared their experiences; to Tab Turner, Nick Poser, Jonathan Sternberg, and Rick Altabef for keeping me legal all these years; Richard Leibner; my computer forensics team and helpers; Les; Don; Owen; Mark; Bill; Sen. Coburn and Keith; Keith and Matt at Javelin; Adam and the entire Harper team; Brian; Jim and Sarah; and my whole supportive family.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The content of this book is based on my own opinions, experiences, and observations. Some quotes contained within are based on my best recollections of the events and, in each instance, accurately reflect the spirit and my sense of the conversations.

Some proceeds from this book are being donated to the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida.

CONTENTS

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Author's Note

Prologue: Big Brother: My Computer’s Intruders

Chapter 1: Media Mojo Lost: Investigative Reporting’s Recession

Chapter 2: Fast and Furious Redux: Inside America’s Deadly Gunwalking Disgrace

Chapter 3: Green Energy Going Red: The Silent Burn of Your Tax Dollars

Chapter 4: Benghazi: The Unanswered Questions

Chapter 5: The Politics of HealthCare.gov (and Covering It)

Chapter 6: I Spy: The Government’s Secrets

Conclusion: The “Sharyl Attkisson Problem”

Index

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

| Big Brother |

My Computer’s Intruders

Reeeeeeeeeee.”

The noise is coming from my personal Apple desktop computer in the small office adjacent to my bedroom. It’s starting up.

On its own.

“Reeeeeee . . . chik chik chik chik,” says the computer as it shakes itself awake.

The electronic sounds stir me from sleep. I squint my eyes at the clock radio on the table next to the bed. The numbers blink back: “3:14 a.m.”

Only a day earlier, my CBS-issued Toshiba laptop, perched at the foot of my bed, had whirred to life on its own. That too had been untouched by human hands. What time was that? I think it was 4 a.m.

Some nights, both computers spark to life, one after the other. A cacophony of microprocessors interrupting the normal sounds of the night. After thirty seconds, maybe a minute, they go back to sleep. I know this is not normal computer behavior.

My husband, a sound sleeper, snores through it all. Half asleep, I try to remember how long ago my computers first started going rogue. A year? Two? It no longer startles me. But it’s definitely piquing my curiosity.

It’s October 2012, and I’ve been digging into the September 11 terrorist attacks on Americans at the U.S. mission in Benghazi, Libya. It’s the most interesting puzzle I’ve come across since the Fast and Furious gunwalking story, which led to international headlines and questions that remain unanswered.

Solving these kinds of puzzles is probably the challenge that drives me most. There’s nothing like an unsolved mystery to keep me at the computer or on the phone until one or two in the morning. Most mysteries can be solved, you just have to find the information. But too often, the keepers of the information don’t want to give it up . . . even when the information belongs to the public.

Now my computers offer a new mystery to unravel. I already had begun mentioning these unusual happenings to acquaintances who work in secretive corners of government and understand such things. Connections I’d met through friends and contacts in the northwest Virginia enclaves. Here, so many work for—or recently retired from—one of the “alphabet agencies.” CIA. FBI. NSA. DIA. They’re concerned about what I’m experiencing. They think something’s going on. Somebody, they tell me, is making my computers behave that way.

They’re also worried about my home phone. It’s practically unusable now. Often, when I call home, it only rings once on the receiving end. But on my end, it keeps ringing and then connects somewhere else. Nobody’s there. Other times, it disconnects in the middle of calls. There are clicks and buzzes. My friends who call hear the strange noises and ask about them. I get used to the routine of callers suggesting, half-jokingly, “Is your phone tapped?” My whole family’s tired of it. Verizon has been to the house over and over again but can’t fix whatever’s wrong.

On top of that, my home alarm system has begun chirping a nightly warning that my phone line is having “trouble” of an unidentified nature. It chirps until I get out of bed and reset it. Every night. Different times.

I’m losing sleep.

I’m the one who tries to get information from the keepers and I can be relentless. That kind of tenacity doesn’t always make friends, not even at CBS News, which has built an impressive record for dogged reporting in the tradition of Edward R. Murrow, Eric Sevareid, and Mike Wallace. But that’s okay. I’m not in journalism to make friends.

My job is to remind politicians and government officials as to who they work for. Some of them have forgotten. They think they personally own your tax dollars. They think they own the information their agencies gather on the public’s behalf. They think they’re entitled to keep that information from the rest of us and—make no mistake—they’re bloody incensed that we want it.

The Benghazi mystery is proving especially difficult. The feds are keeping a suspiciously tight clamp on details. They won’t even say how long the attacks went on or when they ended. What they do reveal sometimes contradicts information provided by their sister agencies. And some of the most basic, important questions? They won’t address at all.

For months, the Obama administration has dismissed all questions as partisan witch-hunting. And why not? That approach has proven successful, at least among some colleagues in the news media. They’re apparently satisfied with the limited answers. They aren’t curious about the gaping holes. The contradictions. They’re part of the club that’s decided only agenda-driven Republicans would be curious about all of that. These journalists don’t need to ask questions about Benghazi at the White House press briefings, at Attorney General Eric Holder’s public appearances, or during President Obama’s limited media availabilities. It might make the administration mad. It might even prompt them to threaten the “access” of uncooperative journalists. Other journalists simply think it would be rude—maybe even silly—to waste time pursuing a topic of such little consequence.

There are so many more important things going on in the world.

But still, I’m curious.

What did the president of the United States do all that night during the attacks? With Americans under siege and a U.S. ambassador missing—later confirmed dead—what actions did the commander in chief take? What decisions did he make?

I’m making slow but steady progress in finding answers to some of the mysteries. Some of my sources are in extremely sensitive positions. They say lies are being told. They’re angry. They want to set the record straight. But they can’t reveal themselves on television. It would end their careers and make them pariahs among their peers. Little by little, with their help, I’m piecing together bits of the puzzle.

T

hose involved in the U.S. response to the attacks tell me that the U.S. government was in sheer chaos that night. Those with knowledge of military assets and Special Forces tell me that resources weren’t fully utilized to try to mount a rescue while the attacks were under way. Those with firsthand knowledge say that the government’s interagency Counterterrorism Security Group (CSG) wasn’t convened, even though presidential directive requires it. Others whisper of the State Department rejecting security requests and overlooking warning signs in the weeks leading up to the attacks.

There are those in government who don’t like it that the sources are talking to me. “Why are they speaking to reporters,” they grumble to each other, “revealing our dirty laundry, telling our secrets?” These are powerful people with important connections.

I start to think that may be why my computers are losing so much sleep at night.

| FIRST WARNINGS

Months before the rest of the world becomes aware of the government’s so-called snooping scandal I already know it’s happening to me.

Snooping scandal.

As serious as the implications are, the media manages to give it a catchy little name. Not so much intruding, trespassing, invading, or spying. Snooping. You know, like a boyfriend snoops around on his girlfriend’s Facebook account. Or kids snoop through the closets for Christmas packages. It’s like dubbing HealthCare.gov’s disastrous launch a “glitch.”

In the fall of 2012, Jeff,* a well-informed acquaintance, is the first to put me on alert. He’s connected to a three-letter agency. He waves me down when he sees me on a public street.

“I’ve been reading your reports online about Benghazi,” he tells me. “It’s pretty incredible. Keep at it. But you’d better watch out.”

I take that as the sort of general remark people often make in jest based on the kind of reporting I do. As in: You’d better watch out for Enron, they have powerful connections. You’d better watch out for the pharmaceutical companies, they have billions of dollars at stake. You’d better watch out for Obama’s Chicago mafia. I hear it all the time.

But Jeff means something more specific.

“You know, the administration is likely monitoring you—based on your reporting. I’m sure you realize that.” He makes deep eye contact for emphasis before adding, “The average American would be shocked at the extent to which this administration is conducting surveillance on private citizens. Spying on them.” In these pre–NSA snooping scandal, pre–Edward Snowden days, it sounds far-fetched. In just a few months, it will sound uncannily prescient.

“Monitoring me—in what way?” I ask.

“Your phones. Your computers. Have you noticed any unusual happenings?”

Yeah, I have. Jeff’s warning sheds new light on all the trouble I’ve been having with my phones and computers. It’s gotten markedly worse over the past year. In fact, by November 2012, there are so many disruptions on my home phone line, I often can’t use it. I call home from my mobile phone and it rings on my end, but not at the house. Or it rings at home once but when my husband or daughter answers, they just hear a dial tone. At the same time, on my end, it keeps ringing and then connects somewhere, just not at my house. Sometimes, when my call connects to that mystery-place-that’s-not-my-house, I hear an electronic sounding buzz. Verizon can’t explain the sounds or the behavior. These strange things happen whether I call from my mobile phones or use my office landlines. It happens to other people who try to call my house, too. When a call does manage to get through, it may disconnect in mid-conversation. Sometimes we hear other voices bleed through in short bursts like an AM radio being tuned.

One night, I’m on my home phone, reviewing a story with a CBS lawyer in New York and he hears the strange noises.

“Is (click) your phone tapped (clickity-click-bzzt)?” he asks.

“People (clickity-bzzt) seem to think so (click-click),” I say.

“Should we speak (click-click) on another line?”

“I don’t think a mobile phone is any better (bzzzzzt) for privacy,” I tell him.

Our computers and televisions use the same Verizon fiber optics FiOS service as does our home phone and they’re acting up, too. And the house alarm going off at night gets me out of bed to scroll through the reason code on the panel to reset it. It makes the same complaint night after night: trouble with the phone line. Two a.m. one night. Three forty-seven a.m. the next. No rhyme or reason.

The television is misbehaving. It spontaneously jitters, mutes, and freeze-frames. My neighbors aren’t experiencing similar interruptions. I try switching out the TV, the FiOS box, and all the cables. Verizon has done troubleshooting ad nauseam during the past year and a half. To no avail.

Then, there are the computers. They’ve taken to turning themselves on and off at night. Not for software updates or the typical, automatic handshakes that devices like to do periodically to let each other know “I’m here.” This is a relatively recent development and it’s grown more frequent. It started with my personal Apple desktop. Later, my CBS News Toshiba laptop joined the party. Knowing little about computer technology, I figure it’s some sort of automated phishing program that’s getting in my computers at night, trolling for passwords and financial information. I feel my information is sufficiently secure due to protections on my system, so I don’t spend too much time worrying about it. But the technical interruptions get to the point where we can’t expect to use the phones, Internet, or television normally.

Around Thanksgiving, a friend tries to make a social call to my home phone line. I see his number on the caller ID but when I pick up, I hear only the familiar clicks and buzzes. He calls back several times but unable to get a clear connection, he jumps in his car and drives over.

“What’s wrong with your phone?” he asks. “It sounds like it’s tapped or something.”

“I don’t know,” I answer. “Verizon can’t fix it. It’s a nuisance.”

“Well, if it’s a tap, it’s a lousy one. If it were any good, you’d never know it was there.”

Numerous sources would tell me the same thing in the coming months. When experts tap your line, you don’t hear a thing. Unless they want you to hear, for example, to intimidate you or scare off your sources.

Well, it’s silly to think that my phones could really be tapped. Or my computers, for that matter. Nonetheless, I tell the friend who’d tried to call my house about the computer anomalies, too.

“If you want to get your computer looked at, I might know someone who can help you out,” he offers. Like so many people in Northern Virginia, he has a trusted connection who has connections to Washington’s spook agencies. I say I’ll think about it.

On one particular night, the computer is closed and on the floor next to my bed. I hear it start up and, as usual, I shake myself awake. I lift my head and see that the screen has lit up even though the top is shut. It does its thing and I roll over and try to go back to sleep. But after a few seconds, I hear the “castle lock” sound. That’s what I call the sound that’s triggered, for example, when I accidentally type in the wrong password while attempting to connect to the secure CBS system.

They’re trying to get into CBS, I think to myself. Hearing the castle lock, I figure they’ve failed. Gotten locked out. Nice try. Only later do I learn that they had no trouble accessing the CBS system. Over and over.

When I describe the computer behavior, my contacts and sources ask me when I first noticed it. I don’t know. I didn’t pay much attention at the time. On the Apple, I figure it was at least 2011. Maybe 2010. My husband would sleep through it. Later, I’d remark to him that the computer woke me up last night.

“Do you think people can use our Internet connection to get into our computers at night and turn them on to look through them?” I’d ask him, thinking only of amateur hackers and spammers.

“Of course they can,” he’d say matter-of

-factly.

The second week of December 2012, my Apple desktop has just had a nighttime session. A night or two later, it’s my CBS News laptop. I look at the clock next to the bed. The green glow of 5:02 a.m. blinks back at me. Later than usual. Considering the discussions I’m now having with my contacts who think I may be tapped, I decide it might be useful to start logging these episodes. But no sooner do I begin this task than the computers simply . . . stop. It’s as if they know I’ve begun tracking them and the jig’s up. The first time I attempt to formally log the activity would be the very last time I’d notice them turning on at night. This time frame, when I noticed the activity halts, December 10 through December 12, 2012, later becomes an important touchstone in the investigation.

| DISAPPEARING ACT

In late December 2012, I take up my friend’s offer to have my computer examined by an inside professional. Arrangements are made for a meeting.

In the meantime, Jeff wants to check out the exterior of my home. To examine the outside connections for the Verizon FiOS line and see if anything looks out of order.

“If you’re being tapped, it’s probably not originating at your house, but I’d like to take a look anyway,” he says.

“Sure, why not.” I don’t think he’ll find anything but there’s no harm in having him look. Maybe I should be more concerned. What if the government is watching me? What if they’re trying to find out who my sources are and what I may be about to report next?

“I did find some irregularities,” Jeff tells me on the phone after inspecting the outside of my home. “It could be nothing, but I’d rather discuss it in person.” We meet at my house and he walks me to a spot in the backyard just outside my garage. His primary concern is a stray cable dangling from the FiOS box attached to the brick wall on the outside of my house. It doesn’t belong.

Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's Washington

Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's Washington